The Sculptures and Objects More Generally

❮ ❯

For three years this enquiry proceeded under the question ‘what happens to sculpture when it is filmed and photographed?’ While this question, in the end, became inadequate to describe the specific trajectory the research took, it was incredibly generative. It enabled me to convey easily a sense of my enquiry to others and, by continually coming back to it again and again, it structured a collection of activities which have ultimately outstripped it and its usefulness, but to which it will always be indebted. The main problem as it turned out was not the question’s breadth (this was always understood), but in its use of the word ‘sculpture’, which in the end seemed to signal something which did not exist. There was no sculpture to begin with that things happened to, no original to which all images could be compared. The sculptures of this research, – and as we shall see this is no simple definition – the things I have made, were not ‘sculpture’ before they were filmed. Conceived of and constructed for the process of filming they are sculpture made to be filmed but also objects made to be sculpture. They are the instigators or loci of a series of practices aimed at generating questions about the nature and possibilities of these objects within an artistic practice structured around the camera. ‘Filming sculpture’ becomes the situation/set-up which organises the production of objects-as-sculpture in ways that throw light on, or open questions around, both sculpture (as a particular category of object) and objects more generally....

We therefore turn our attention toward the ‘sculptures’ of this research and to the question of what they are, how they should be considered, and what exactly is the function of their relationship to the camera.

It seems important that these objects have been physically constructed or formed. They are not consumable objects plucked from the world in the sense of the ‘readymade’, bestowed with sculpture-hood by the art context. Nor are they everyday objects explored for their physical and imaginative possibilities such as in the film Plasma Vista (2016) by Cockings and Fleuriot, or the films of my own collaborator Claire Undy. Neither are they assemblages of objects presented as sculpture, like the photographic series Equilibre (1984-7) by Fischli/Weiss, where the camera is used to bestow a permanence on momentary or short-lived constructions. Similarly they are not objects from other disciplines such as design or architecture, which are of particular formal or aesthetic significance that the camera can draw attention to, like Simon Martin’s Carlton (2006), in which a piece of post-modern furniture is beheld enigmatically and beautifully on film, or transformed by the use of lighting like Hollis Frampton’s film Lemon (1969), in which a giant fruit is slowly revealed as if it were a moonrise. They are not interventions into everyday life recorded by the camera, such as Cats and Watermelons (1992) by Gabriel Orozco, or the films of Francis Alys, or performance acts which have been documented, like those of Bruce Nauman and Claes Oldenburg.

Despite not being exactly like any of these practices, the current research benefits from engagement with them all. It borrows strategies and processes and applies them to its specific concern: how the physical forming of a sculpture can be placed in a reciprocal dynamic with the act of filming. The question is not whether the camera legitimises these things as sculpture, but rather in what ways can the dynamic of sculpture and camera be employed in order to explore their combined possibilities.

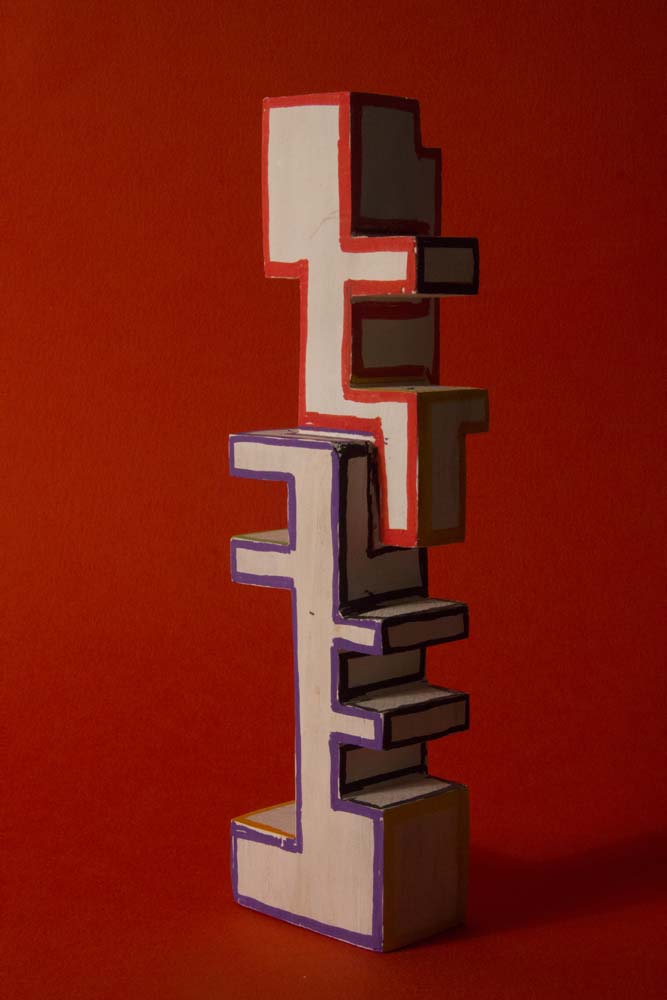

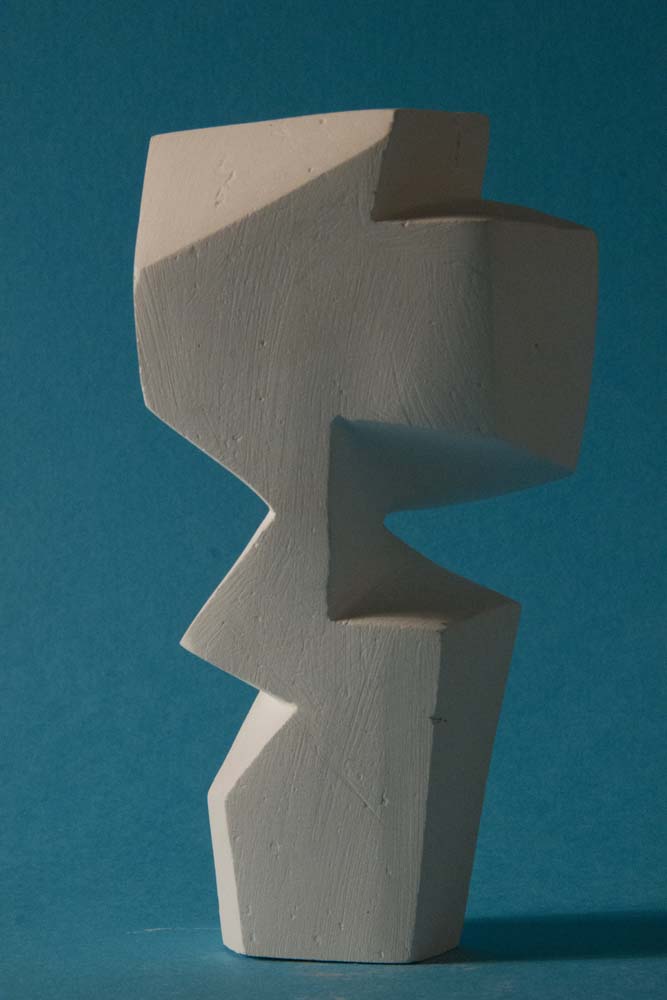

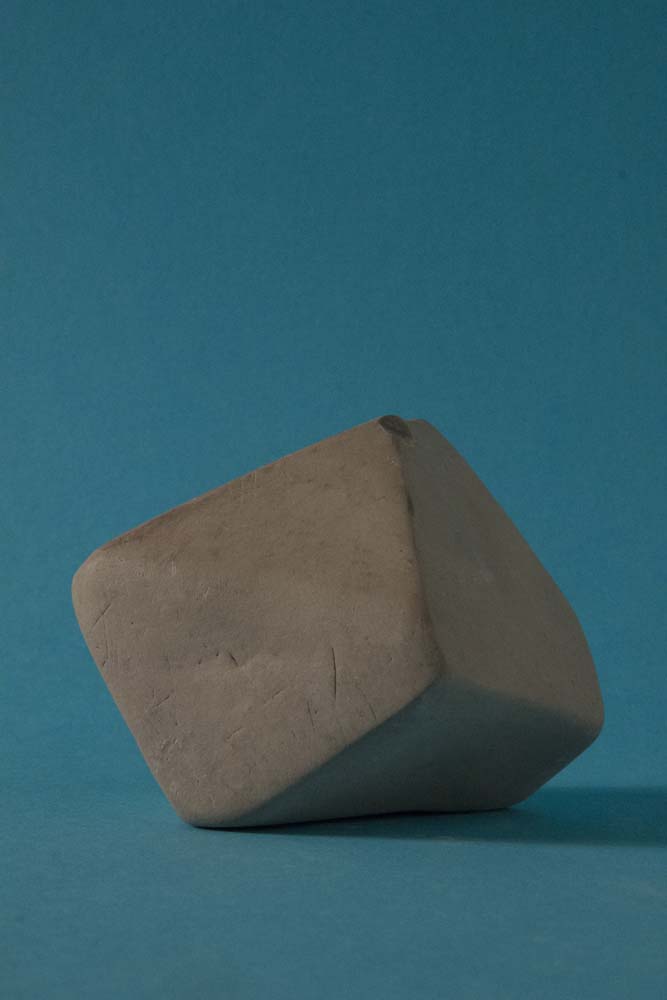

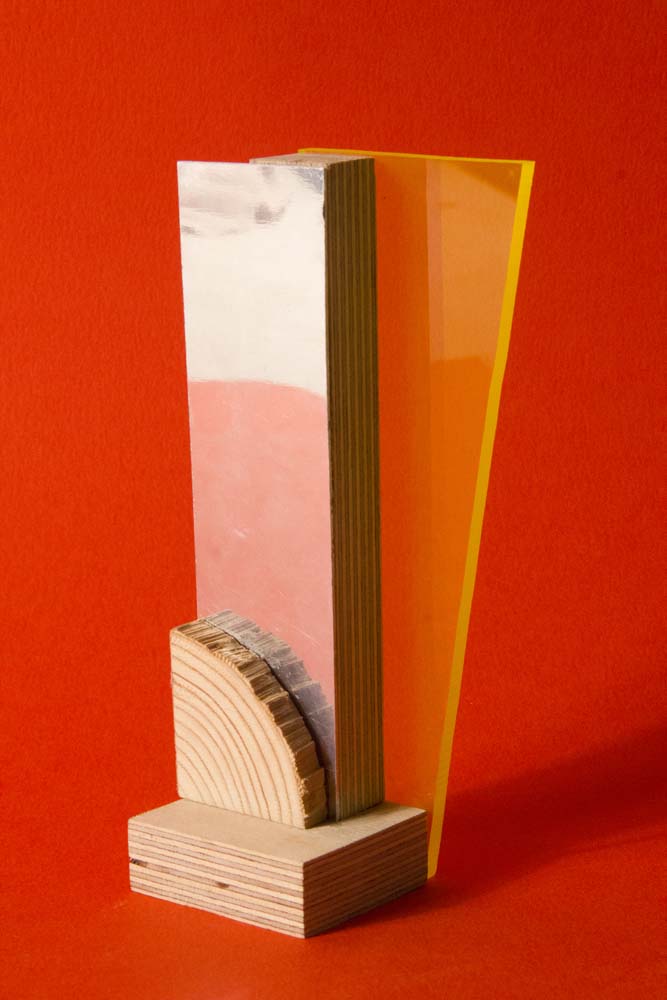

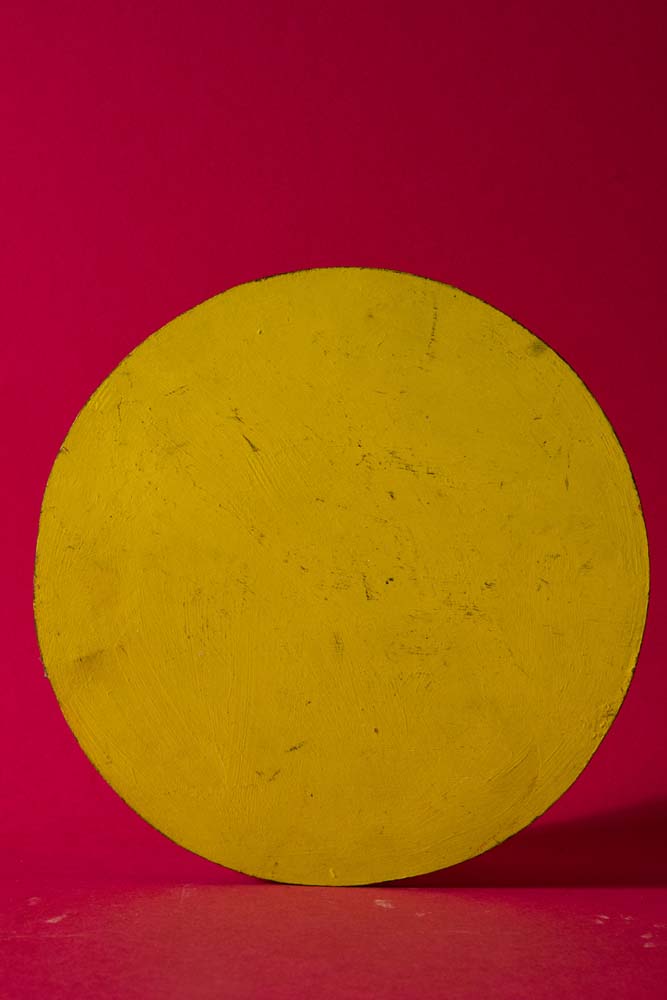

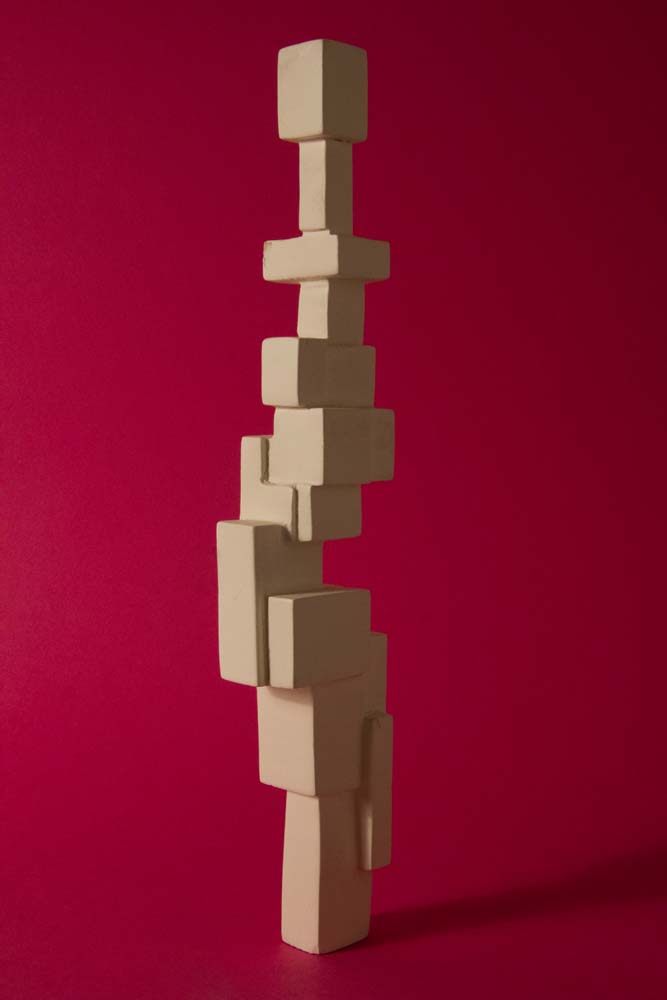

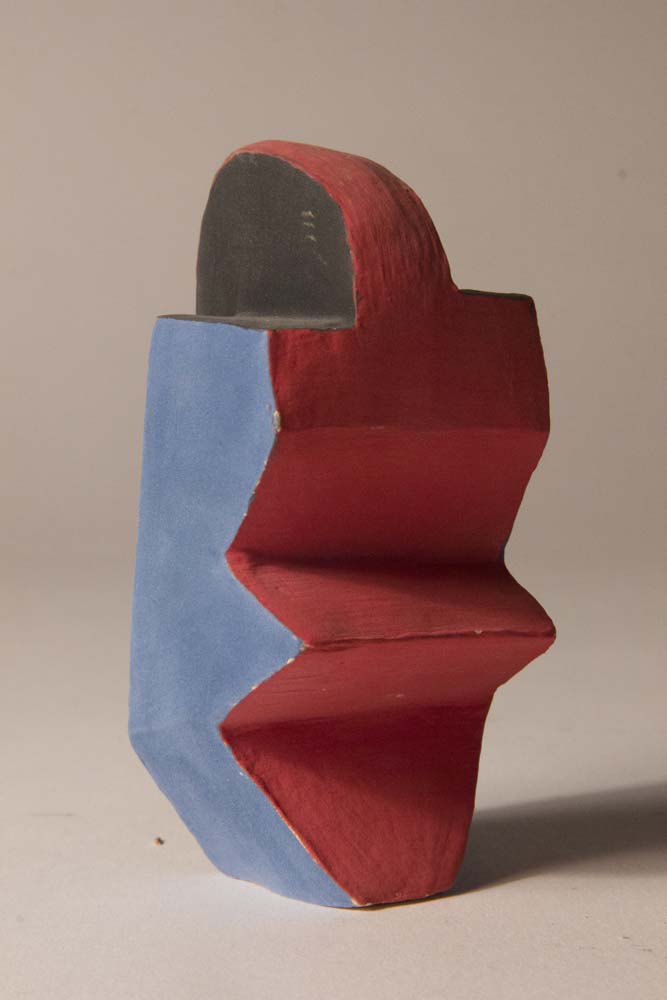

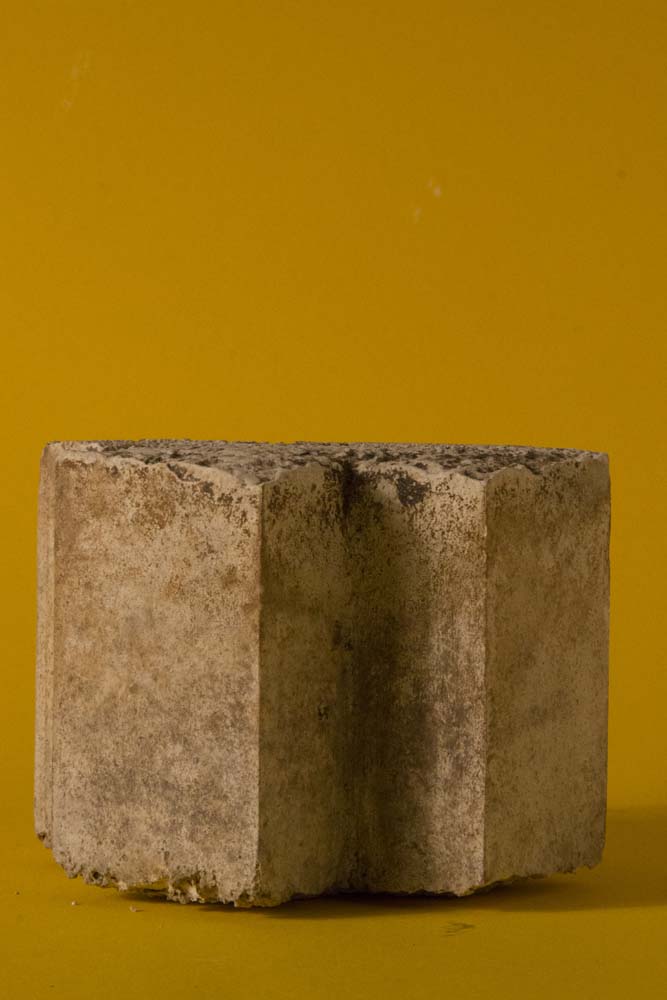

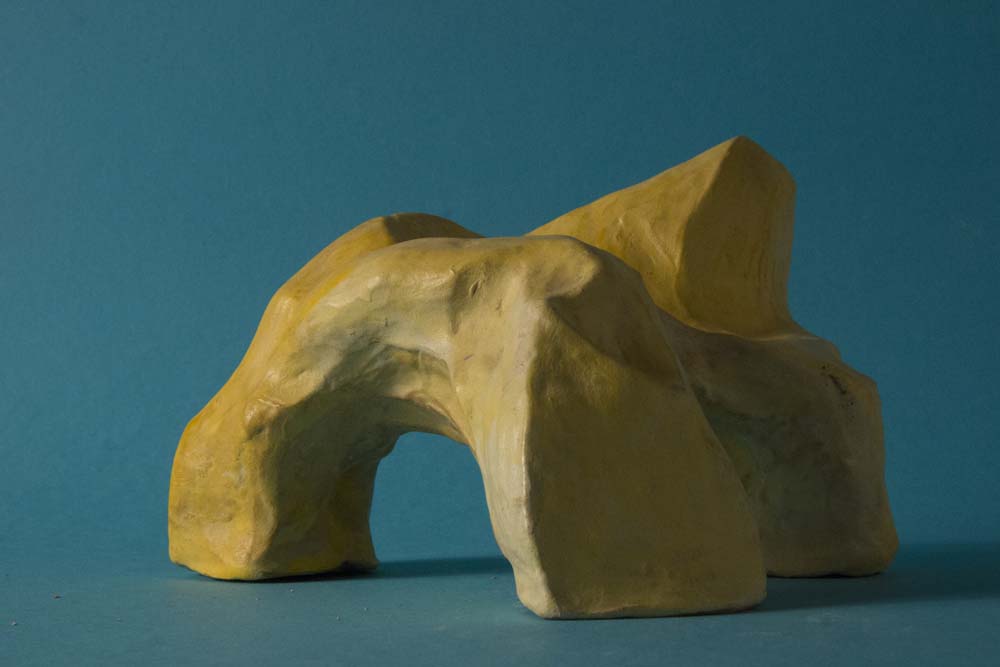

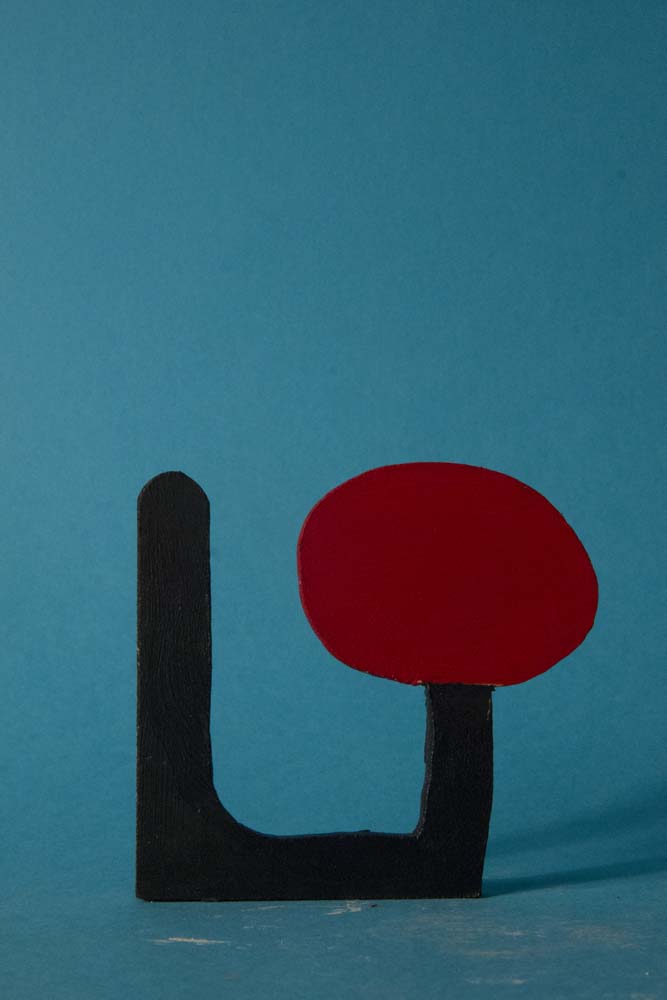

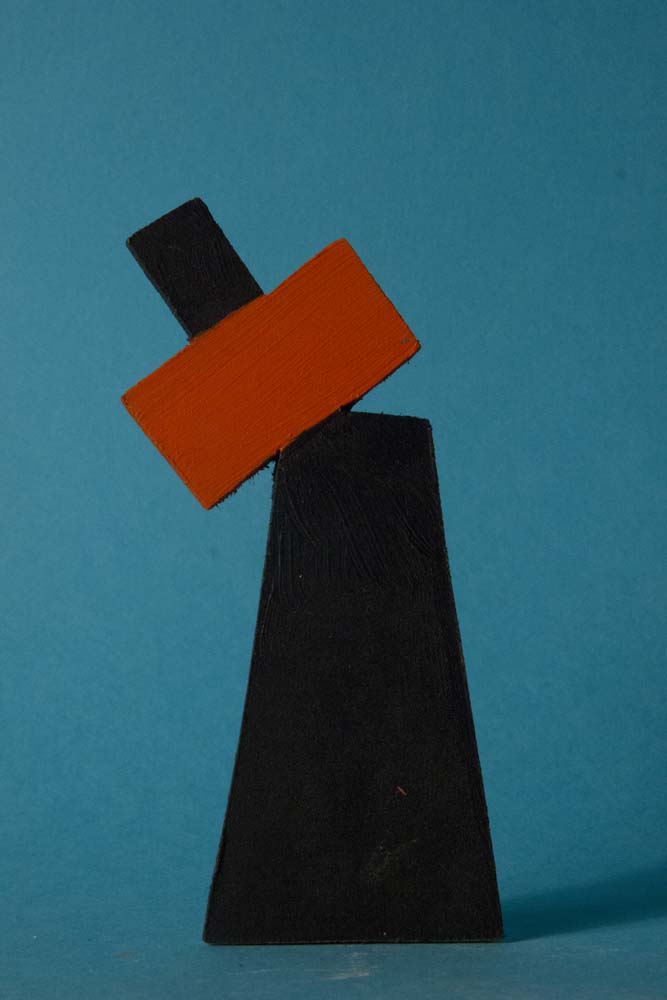

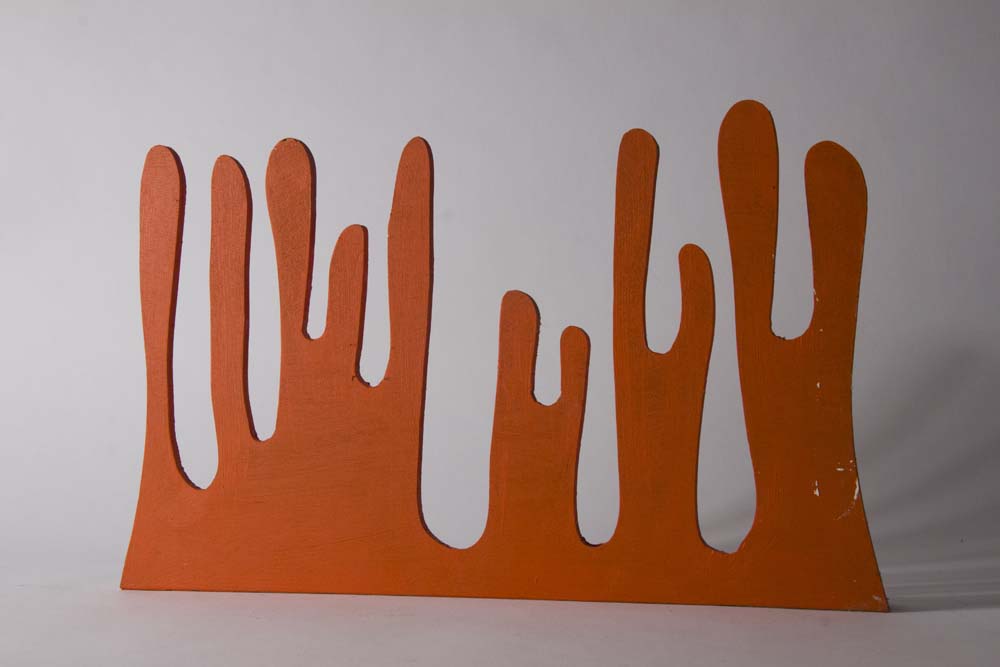

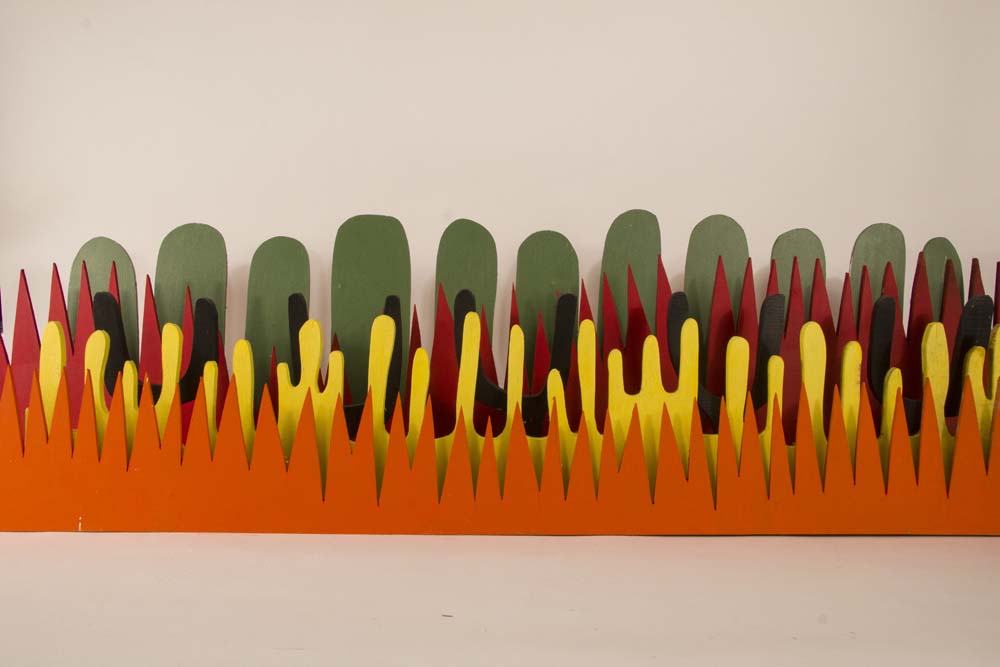

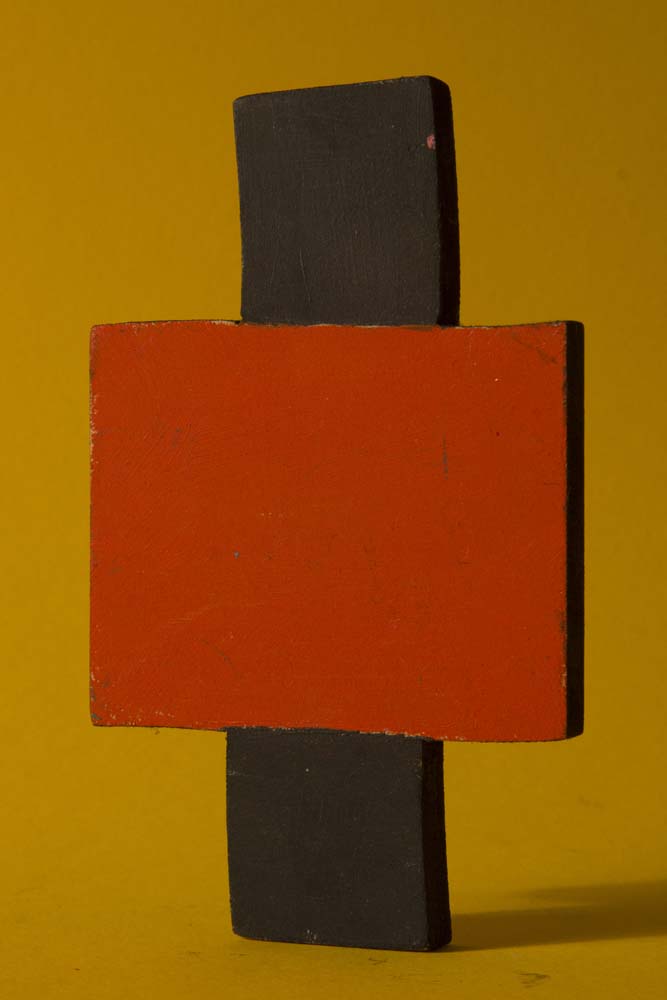

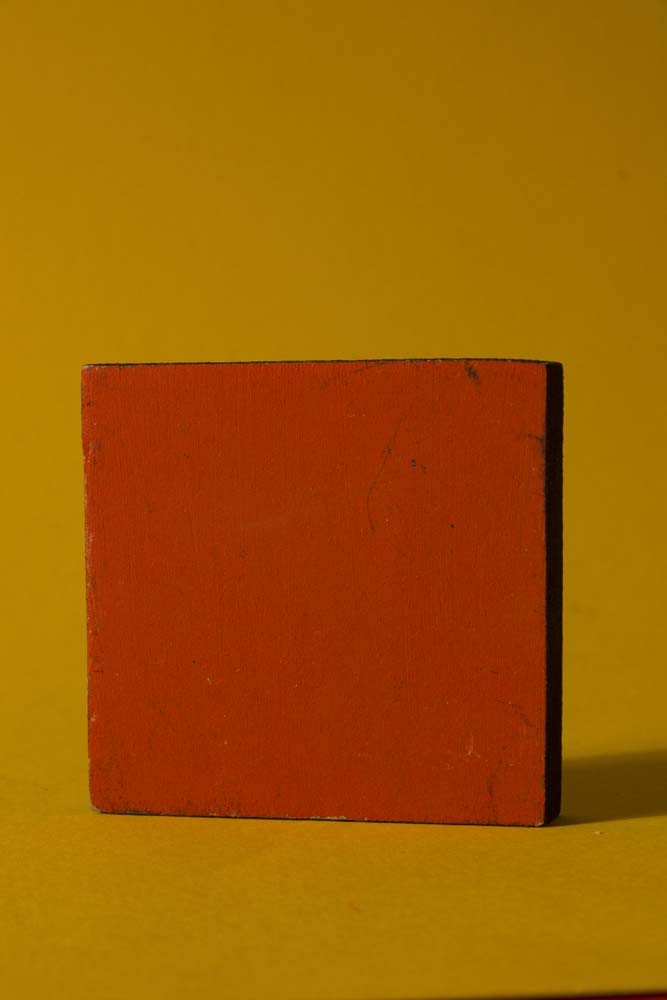

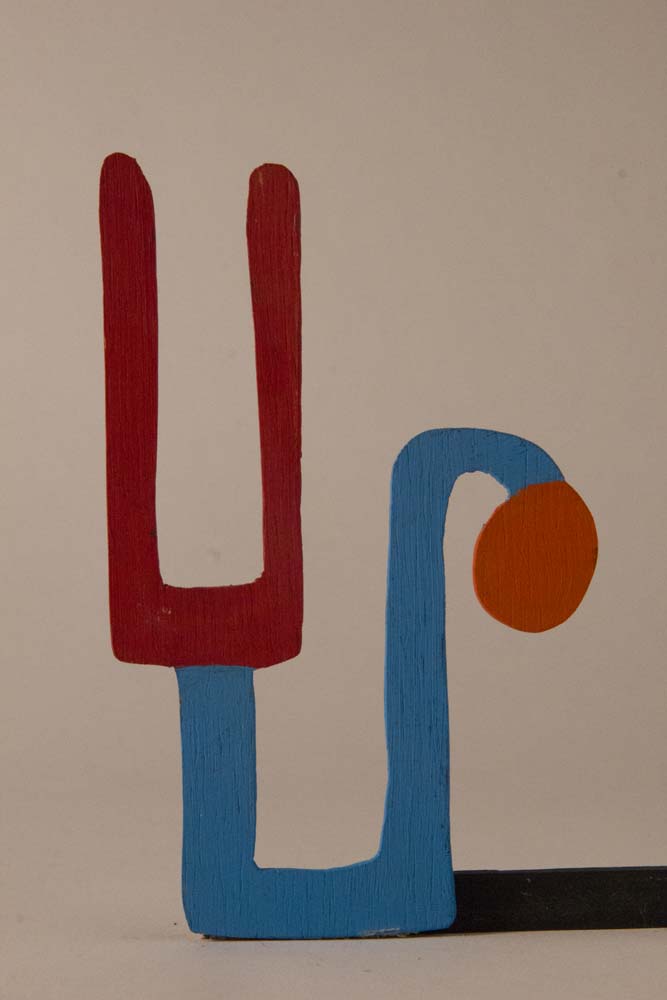

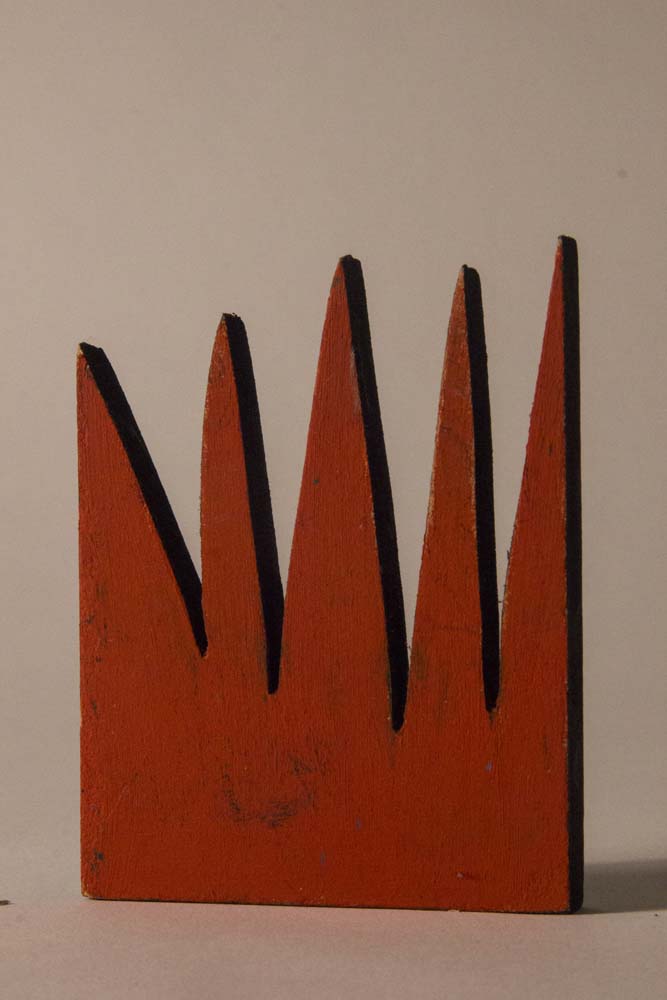

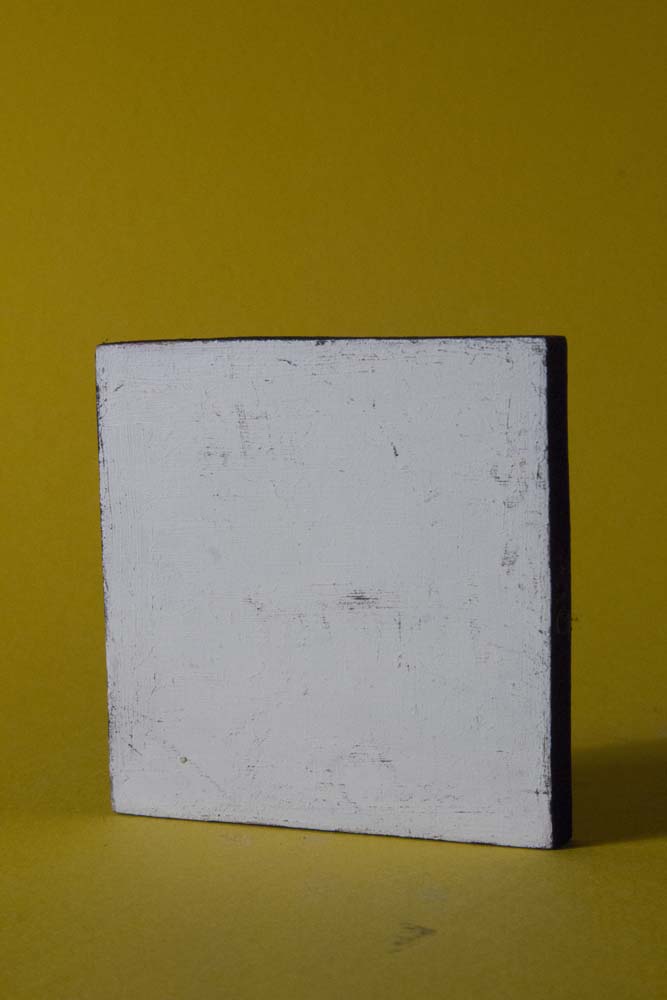

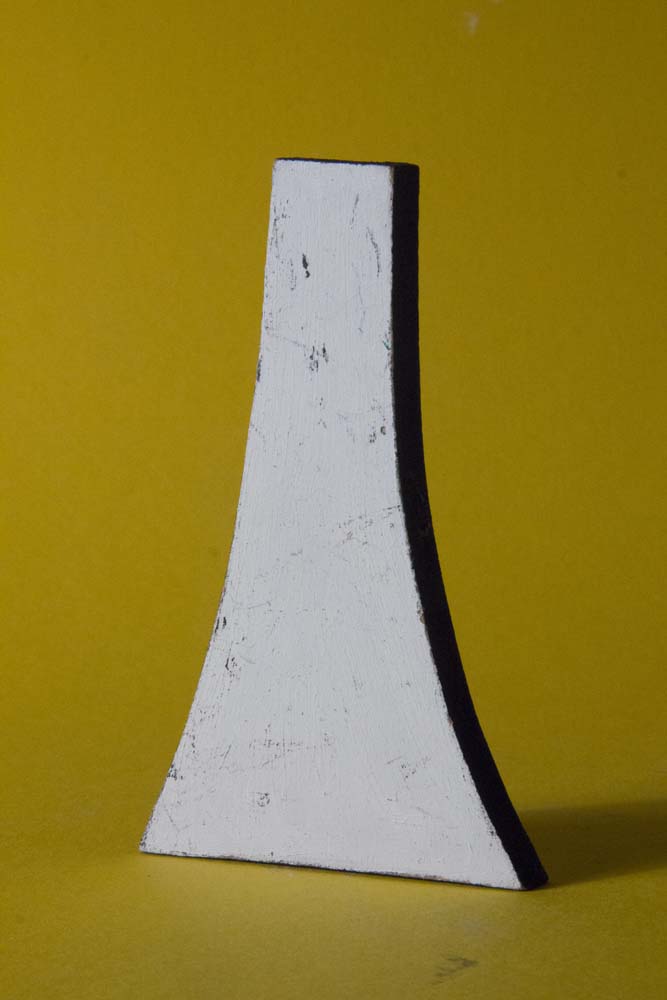

The objects of this research have been made – constructed, modelled, carved, cut – by the artist in order to be filmed and this gives them a very particular quality and status. Although they are not intended for presentation within a gallery space, they do look very much like sculpture. They are things which have mass and weight and particular aesthetic qualities of a sculptural kind.

A series of questions then proliferate: Does this sculptureishness pre-exist the filming of the objects or is it conferred on the objects by the process itself? Are aspects of both objects and process conspiring to produce sculpture effects? Are they significantly different things than they would be if they were intended for a more traditional mode of display?

This ontological questioning owes much to readings in contemporary metaphysics and phenomenology. This is not questioning that demands definitive answering, but has been used to tease out the particularities of the research process, and of the objects and practices which comprise it. We will return to the particular properties which might be seen to characterise these objects as ‘sculpture’, and turn now to their relationship to the process of filming, and questions about the nature of objects in general. When we talk of these sculptures what exactly is it we refer to, the physical object which is placed in front of the camera, or the thing which reaches the viewer on or through film? Are these to be considered different objects, or instances of the same? Do they persist as relatively stable entities through the process of filming or are they transformed into something substantially different to that which they originally were?

THE REAL AND THE SENSUAL

Object Oriented Ontology and the related areas of Speculative Realism, Thing Theory and Vibrant Materialism, have all come to prominence in recent years, and have been widely embraced by the art world. What unites these philosophies is their consideration of a world of objects existing beyond human access, in which objects have hidden depths and vitality, or exist alongside humans in networks where agency is dispersed.

A number of strong criticisms have been made of these philosophies, including that they have been all too easily co-opted by the art market and ‘stripped for buzzwords’ (Apter etal. 2016, p.8) in order to reaffirm the commodity value of art works, and that by focusing on objects, these philosophies ignore the still very real and ongoing political inequalities that exist for people, which post- structuralist inspired theories did so much to challenge.

The use of vivid and poetic language employed by many of these writers can also be problematic as it can be seen to lead to a kind of object fetishism, which marvels at the glories of matter and material in a mysterious and anthropomorphic, even quasi-religious, manner. What D. Graham Burnett describes as, ‘barely secularised forms of spiritual striving.’(ibid, p. 20) The refreshed attention given by artists and curators to the potency and depth of art objects in the wake of these philosophies, would seem to support this idea and can easily be seen as a form of reification, if not a directly monetary one. This aside, by shifting our focus away from the ways in which sculptures are made and intended by human agency, and instead considering the latent qualities and dynamics between sculpture and camera, and the ways in which they impact upon the various encounters that make up the full scope of the art work – from conception, construction, filming and editing to its meeting with a viewer - these philosophies offer us the opportunity to form a deep and complex understanding of this process and the objects that constitute it. As Armen Avanessian writes, ‘[t]he thing about the toy truck, for the magnet, is the iron. The thing about it for the girl (just now) is the sound the wheels make when they spin really fast. The thing about it, for her mother, is the fact that her own father once played with it, found it, repaired and repainted it (yellow). The thing about it, for the cat, is that at any moment it may dash like a rodent. Some latent thing about the object must be catalyzed by an encounter, and yet: that very thing catalyzes the encounter. (ibid p. 8)

This duality, or paradox is at the heart of Graham Harman’s Object Oriented Ontology, which sees objects as both embedded within a field of relationality and coherent as things in themselves. In order to articulate this joint existence, he posits two types of object, the ‘real’ and the ‘sensual’. The real object is that which forever withdraws, exceeding any relation. The sensual object is that which is created within the relational encounter. These two facets of the same thing allow objects to appear differently, dependant on situation and circumstance, without the coherence of the object itself being threatened. Here the tree is the same tree in summer and in winter, with or without foliage, from close up and at a distance. This is because the tree has a reality which exists beyond any single perspective or perception. Objects therefore, have two types of quality. Those which are susceptible to change and which the object can withstand, such as variations in light or the loss of leaves, and those which are essential to it. Here we might imagine that a tree reduced to firewood or to ash, is no longer a tree. Harman writes that accidental qualities ‘can be shifted nearly at will without affecting the character of the object. Yet the same is obviously not true of its essential features, which the object desperately needs in order to be what it is.’ (Harman 2011, p. 27)

In the context of this research, a model is offered with which to consider the sculpture on film. We could describe the sculpture made to be filmed as the ‘real’ object, which when filmed is given a number of accidental features which inflect our perceptions of them, but which the object can survive – we might think of the mottled texture of 16mm film, the use of harsh lighting, or different camera angles. The object is changed but not unrecognisable. The film could be seen to offer the viewer a series of sensual profiles in a similar way to that which we would find were we to encounter the object in physical reality. What is interesting is that Harman sees these sensual profiles as infinite possibilities. Each and every perception (and this goes for interactions between inanimate objects as well) unlocks only certain features of the object. This allows us to think of the process of filming, not as one of loss – the compacting of three dimensions into two, the fixing of a particular spatial and temporal view - but of unlocking features of the object which may otherwise have not come into view, for example the intense sense of texture that can be produced by harsh lighting and extreme close-up, or the seductive quality of a white, angular object against a stark black background.

For Harman, objects are only ever encountered as sensuous profiles and as such our perception of objects is inevitably partial and our expressions of them – their descriptions or representations in art, philosophy or science - can produce only caricatures, partial renderings masquerading as fully present. The use of the term caricature is, however, somewhat misleading as it suggests that sensual objects as they are perceived are in some way superficial, trivial and simplistic. In fact, the sensual encounter can be multi-layered, deep and complex, a swirl of accidental and essential features, but there are always further possibilities which will be revealed in other encounters. The object is never exhausted.

The universe is thus full of objects which continually withdraw, as there are always aspects of the object which do not present themselves in any single encounter. By this reckoning there could be an infinite number of films made of an object, each unlocking new and different aspects of the thing, never exhausting its possibilities. Harman has more recently replaced his use of the word ‘withdraw’ with that of ‘withhold’, but both have the same mysterious connotation which is appealing in relation to the current research. Art objects are often thought of as compelling because of their depth and inscrutability. The project of art history is in a sense the quest to delve into these myriad possibilities. In this sense however, it is the art historian who is actively probing the work, which may otherwise be considered stable, fixed and complete. In Harman’s hands, it is the object that is the one doing at least some of the work of withholding and revealing, the process is a dynamic one, characterised by negotiation and collaboration.

The complex physical interrelation between camera and object may be further developed in relation to Merleau-Ponty’s evocative description in Eye and Mind (1993) of seeing the tiles at the bottom of a swimming pool: ‘When through the water’s thickness I see the tiling at the bottom of the pool, I do not see it despite the water and the reflections there; I see it through them and because of them.’ (Merleau-Ponty 1993, p. 182) Rather than obscuring the full reality of the object it is the stuff which surrounds it which enables the encounter.

Consider light rather than water. The particular colour frequency may affect the way in which an object is seen, without it there would be no sight. Here the object is inseparable from the watery medium which is at once transparent and viscose. We might see a similar conception in Husserl’s notion that we do not see black, we see the black of ink, or the black of tar, except here the focus is reversed. In both cases objects and qualities are intertwined and inseparable and always embedded within a wider perceptual reality or world, which includes the body, prior experience and socio-historical, cultural and technological conditions. These things are inseparable in our perception.

A similar operation is at work in Harman’s critique of scientific rationalism, which he describes as undermining the object by searching for a more basic reality beneath its surface, and philosophies of relation, for overmining the object, reducing it to its position within a contextual network. Instead he sees the object as caught in a dynamic relation between its inherent reality and the specifics of the situation in which it is found.

An argument could be made here from a Marxist perspective that Harman’s ontology ignores history, or at least subsumes it within the generalising framework of objects and relations on the one hand and objects and qualities on the other. If we consider the reality of objects (and sculptures more particularly) within the frame of art history or culture more generally, then existing in a highly developed consumer society, as we do in the West, is yet another pool through which we see and into which all objects are immersed. This includes multiple discourses from the financial, economic, personal and ecological. The endangered tree has a different patina to it than the common one: its material presence is altered by countless contextual relations.

More surprisingly in Harman’s reckoning, every relation no matter how trivial creates a new object, as within each sensual encounter there are aspects which do not come to light and must, in Harman’s reckoning, constitute a new real object. This makes for a complex situation when filming sculpture. It would appear that in each encounter between sculpture and camera both new sensual and real objects are produced. There are two real objects to begin with: the camera and that which is placed in front of it. The sensual object is what is recorded: an image of the object placed in front of the camera. A new real object is produced: the film which then goes on to produce sensual profiles when encountered by different viewers under different circumstances (more sensual objects).

But there is also the sculpture pictured within the film, which is where the real discoveries of this research may lie. Is this merely another sensual object, one of many potential caricatures of the ‘real’ thing that exists as a physical reality somewhere beyond the film’s reproduction? Or has something new been created, something with its own distinct reality?

If we think of the process of filming as a transformative act, one which not only changes the appearance of the sculpture but potentially transforms the sculpture-like object, the thing made to be filmed but not exhibited, into something that is recognised as sculpture, then something more profound is taking place. The film both reveals new aspects of the sculpture/object and creates a new object: the object as sculpture.

Harman’s litmus test for a real object is whether it has qualities which exceed the sensual encounter. The question is whether the pictured object is all used up when it meets the viewer – does the camera lock down a particular and partial view which is grasped in the same way no matter how, where and in what way it reaches the viewer - or can different qualities be perceived in different circumstances or modes of viewing? For example, if it is projected on a large screen, or on a hand-held device, shown physically side by side with other works or sequenced as part of a larger film.

To further complicate matters, I would suggest that this is not a temporal transformation. The object is not simply an object which is then transformed, butterfly-like, by the process of filming. By being a sculpture made to be filmed, the object owes its sculpturehood to the camera from the very outset, with its own highly-particularised reality. We can then see that we have only one object: the sculpture made to be filmed which can be encountered sensuously by the camera, the artist, the viewer and the workshop participant, in actuality, or on film, each iteration revealing different aspects inherent to the infinitely withdrawn, or withheld ‘real’ object.

Whether we think of the sculpture made to be filmed as a singular real object with a multitude of potential actualisations, or as the process of filming creating a new object, these lines of thought allow us to imagine the confluence of object and camera as a constitutive act, in which something is produced which exceeds conventional understandings of both camera, as that which sees and reproduces, and sculpture, as that which has a singular physical reality outside of the film process.

It may also be that the camera alone does not have the power to confer sculpturehood upon these objects. It is part of a contextual framework which designates certain objects as sculpture, combined with certain sculptural qualities of the object itself. This includes among others, the figure of the artist, the recognition of film and video as an artistic medium, the context in which the work is encountered, and the institutional framing. Rather than trying to make a claim as to whether the pictured sculpture is a sensual or real object, this line of enquiry helps us to form an understanding of the complexity of the relationship between the many factors which condition the work with the moment of filming at the centre.

Rather than seeing the camera and sculpture standing in fixed relations, augmented by human agency, the camera perhaps being seen for its utility in the act of creating images, conceived of and realised by the camera operator and equally the sculpture as a piece of, or combination of, physical materials, forged by or subjected to human will, we can focus our attention on the qualities that each bring to the situation. The ways in which they condition or inflect our approach and understanding of them as entities with a certain degree of agency. Both in their physical, sensual reality and in the ways in which they embody certain aspects of culture more generally. This can lead us both to consider Michel Serres’ concept of the quasi-object and Willem Flusser’s description of the camera as an apparatus encoded with a pre-given set of cultural instructions which the photographer must negotiate.

Flusser writes that, before the industrial revolution, tools were used by humans as extensions of the body. In industrialised capitalist society, however, the human became a function of the machine. The camera operator is thus a functionary who plays with the machine in order to discover its possibilities, which are already pre-determined by the concepts by which the machine was constructed. The photographer (and we may extend this to film-er/video-er and artist) ‘plays’ with the apparatus, which by inference involves playing with the symbols which are programmed into it by ‘meta-programs’ of ever increasing scale – from the science of optics to economics. Sounding remarkably like Harman, Flusser writes, ‘The possibilities within it [the camera] have to transcend the ability of the functionary to exhaust them [...] no photographer, not even the totality of photographers, can entirely get to the bottom of what the [...] camera is up to. It is a black box.‘ (Flusser 1984, p. 27)

This Marxist view has similarities with Michel Serres’ description of the quasi- object. Like Flusser’s apparatus, the quasi-object structures a game conferring subjecthood upon the players. Speaking of a game in which people must pass around a button or slipper without being caught, Serres writes, ‘[t]his quasi- object, when being passed, makes the collective, if it stops, it makes the individual.’(Serres 1982, p. 225) The subject (or subjects) and the object are here mutually constitutive although, as he says of the football, it is the players that follow the ball not the ball that follows the players. ‘Playing is nothing else but making oneself the attribute of the ball as a substance.’ (ibid, p. 226) As with Harman’s objects, Serres is concerned both with the quasi-object as an entity in itself and as a relation: ‘Being or relating, that is the whole question’ (ibid, p. 224)

OBJECTS AS AGENTS

Something similar to Serres’ quasi-object can be found in the concept of indexical agency in Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency: an anthropological theory (1998). Concerned not with philosophical classification, nor sociological concern with institutions and systems, but rather with causal relations happening in real time, Gell shows that objects can be seen as embodying a dispersed social agency. In the first instance this can be seen as a question of identity: for Gell the soldier cannot be a soldier without rifle and land mine, objects which enable him/her to express their causal agency and retain a connection to them beyond their direct presence. Thus the landmine explodes despite the soldier’s absence, but they are nevertheless the agent of this destruction and the harm it may cause. The landmine functions as an index because this causal agency is seen as directly imprinted upon or expressed through the object. It is also the case that ‘agents’ and ‘patients’, as he calls the affective and affected parties in any social relation, continually interact though physical substrates (the body, tools, the material environment) without which no action could be set in motion. Actors in social relations (which include objects) continually slip back and forth between agent and patient status. Importantly for us, Gell talks not in philosophical but biographical terms. For him it is of no consequence that his car does not possess agency in the philosophical sense, what is important is that in day to day life the car is treated by him and his family as if it had partial agency. It is what they rely on to get around: if it were to break down he would consider this an affront; he may even blame the car or kick it; it is even referred to affectionally by a nickname. If we think back to artist Jo Addison’s description of learning her sculptures by making them, we may find something similar in operation. For her, in practice, the objects she makes are attributed a kind of agency, they direct her material investigations, they ‘tell her’ how to progress. More prosaically we might say that the material properties of the objects she creates impact upon her handling and forming of them. They push back. They will hold certain forms and not others. The process of making thus becomes a back and forth of agency, as the agent-patient relationship flips back and forth between artist and object.

Gell also notes that most art works are made with their reception in mind and that the works reception itself may be activated as a type of agency, which is recognised within the object as an index. We might see something of this kind played out in Eva Rothschilds’ film Boys and Sculpture (2012). One by one, then in small groups, a dozen or so boys between the ages of ten and twelve are allowed into a gallery full of imposing angular Modernist-influenced sculptures. They begin walking slowly around, looking at the sculptures from what might be thought a respectful distance - no doubt one learned from social convention, but also inferred from the size and imposing aesthetic of the sculptures themselves. Only as more boys enter the room do they begin to circle around particular works until, after what might be ten minutes, someone touches the tall piece at the back of the room and rather than resist imperviously, it yields to the touch, swaying delightfully like a tree in the wind. At this moment, what might be interpreted as the invitation of the work completely changes. What at first seemed solid, imposing objects, bend to the touch, and are inevitably pushed some more until the whole sculpture collapses, and its spherical pieces become balls to be kicked. After this the entire exhibition is dismantled, knocked over, used as swords and reassembled into new objects. There were no instructions given before the boys entered the room, and it is therefore hard to view these sculptures as completely passive objects whose meaning is given to them solely by their beholder. They, or at least the artist, anticipated certain types of interaction and built these into the fabric, the physical materiality of the sculptures themselves. Graham Harman, Bill Brown or Jane Bennett might see this as evidencing the power of objects themselves. For Gell they might evidence a dispersed agency within a social milieu, conditioned and enabled both by the presence of humans and of meaningful and causal social objects: an indexical agency possessed by the sculptures which lives on beyond the artist’s direct presence. This points to the ways in which objects and people, together, create interactions, practices and meanings within particular social contexts.

We can make a connection here between Gell’s indexical agency and Flusser’s understanding of the way in which the camera embodies a program itself inscribed within a larger social, cultural and economic context, to which the operator is subject. Whilst Gell is interested in day to day human interactions, Flusser’s concept focuses on the ways in which the everyday dealings of the camera operator are determined, to a certain extent, by the possibilities inherent in the object itself. Possibilities which are culturally and institutionally determined. Each author’s conception offers something slightly different. With Flusser the object’s power appears to come from within the ‘black box’, whereas for Gell, its power is external and has to do with the way it interacts and connects with a pre-existing social context.

In both cases, the object has a power, which might be seen both to play an essential role in, or even structure, certain social practices and, as made clear in both Michel Serres’ theory of the quasi-object and Gell’s idea of dispersed agency, has some role in the construction of subjectivity. The artist is not an artist in principle, but only in as much as the things they make, engage with, or have some kind of impact within the social context of ‘art’. Equally the viewer of art is only a viewer in as much as they can view and engage with art works and practices.

This may be extended by considering Robert Morris’s infamous exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1971, for which he created a collection of large objects designed to prompt physical interaction from the viewer. As Morris wrote to the exhibition organiser ‘the show is more environmental than object-like, offers more the possibility – or even necessity – of physically moving over, in, around, rather than detached viewing. Personally, I’d rather break my arm falling off a platform than spend an hour in detached contemplation of a Matisse.’ (cited in Floe 2014) This wish was soon fulfilled when, during the opening and subsequent days, before the exhibition was prematurely closed, audiences clambered, leapt and variously interacted with such force and exuberance that many sustained minor injuries and the work became damaged. Despite Morris’ quip, he actually intended the work to be interacted with in a far more considered and reverent way, one of, as Hilary Floe puts it, ‘quiet phenomenological self-discovery’(ibid), evidenced in the film Neo Classic (1971) that Morris made shortly before the opening in which three dancers interacted with the slopes, balls and cylinders in a measured, almost spiritual, manner. It seems Morris had misjudged both the expectations of the audience and the invitation of the objects. For example, two heavy balls attached by rope, intended to be dragged meditatively along the floor, were reportedly held aloft and swung around one ‘viewer’s’ head. This begs the question as to the indexical relationship of author and art work. Does the work here possess a borrowed-agency or rather its own unanticipated one, forged not in the dynamic of creator and creation, but by sculpture and viewer? Could this perhaps be described as an unintended indexicality? Gell acknowledges this unanticipated agency. For him intention is of less concern than causation and, as such, it was Morris who ‘caused’ the events, even if they confounded his expectations. This is to simplify however, because as we have seen, Gell understands multiple agencies and indexes to be at play at any moment, which here might include that of the artist, the gallery, the building itself, the sculptures and the audience, all continually swapping between agent and patient, actor and acted upon. What we have is not a one-way street of agency and causation, but a continual flow and negotiation, between humans and objects of their concern, within wider social contexts and extra-material qualities of institutions, practices and behaviours, which make what takes place take place.

Within the context of research which considers the relation of sculpture and camera we are now in a complex situation. How do these objects interact? If the sculpture is the quasi-object then it structures a situation, the camera looks at it, as does the artist, but equally the camera brings with it its own coded identity in which the artist – now seen as an operator or functionary – must ‘play’ within the system that the camera embodies. Having created the sculpture in the first place the artist has sent it forth as an index of their agency, but then they approach the sculpture anew, attempting as far as possible to put aside pre-determined ideas of how the object will interact with the camera, the camera with the object. There is a sense of unlocking. Of facilitating the encounter by these two objects both imbued with agency, socially, culturally and economically encoded, structuring a game which the artist, having initiated in the first place, must now be at least in part subjected.

This might be seen as a feedback loop in which the unconscious social context produces sculptures which themselves prompt or produce certain ways of being towards them. It might also be that previously undetermined and unexpected qualities of the sculptures are catalysed within the encounter, by one who is primed to recognise and respond to particular qualities and affordances, due to the social milieu in which the whole activity is situated.

In the practical research setting, these theories, philosophies, and the vocabulary they employ, can be useful for the imaginative possibilities they open up. By thinking of the object and camera as agents in the creation of something beyond the artist’s direct control, where each may demand things of the other, or in which it is asked what does this object afford, what does it offer, what does it want?, new ways of acting towards, experiencing or exploring both sculpture and camera can be discovered. This is not, in any way to diminish the privileged position of the human in these practices, but to acknowledge the role that objects play in the construction of our experience and our lived possibilities.

In the process of making art and particularly art research, in which new knowledge is sought, it is a reminder not to dominate the things with which we work with pre-conceived ideas or expectations, but to be open to their potential whether material, physical, kinetic, associative, anthropomorphic, historically or culturally significant. It enables us to think of sculpture – or at least the sculptures made to be filmed – not only as a kind of specialised object made for contemplation or other higher aesthetic purposes, but as objects with a certain degree of agency within certain social settings – the film studio, the gallery, the workshop, - which can be used by the artist researcher (as well as other diverse audiences) to prompt physical, material and imaginative exploration, which allow us to think about the nature of sculptures, camera objects and social interactions more generally.

REPRESENTATIONS

We have so far addressed the question of what these objects, presented to and by the camera are, in terms of their objecthood and their power or agency within certain social situations. We will now return to the particular objects of this research and ask again, are they sculpture?

Let us take two specific instances to try and figure this out. Firstly, if we return to Eva Rothschild’s sculptures, which ‘appear’ to be solid, imposing and impervious objects, but turn out to be made of pliable and dissemble-able materials, we might think of these not as ‘sculptures’ as we might Rothschild’s other sculptural output, which are indeed solid, and intended for traditional gallery ‘viewing’, but as representations, both of angular, modernist constructions and also of her own work. These are objects designed to be physically touched and taken apart. They ‘look’ like Eva Rothschild sculptures, but their materials and their purpose differ from that of more traditional solid sculptural exhibits. As with the objects that populate my own films, we might ask, are these really sculptures? Are they more like props or prompts or objects of play – quasi-objects which construct a subject: that of a young boy left unattended in a gallery who goes on to cause havoc. Should these ‘sculptures’ be considered art works in themselves? The art work Rothschild chose to present to the public at large is the film, the record of the boys’ interactions made without their knowing. This sets them apart from Robert Morris’ Tate Gallery installation in which the objects were presented as sculpture, albeit sculpture that invited a different mode of interaction from that of convention. Morris’ sculptures were encountered by the public within the gallery, whereas Rothschild’s only appear within the film. Exactly what constitutes these things as ‘sculpture’ may be a matter of both the artists’ framing of the work and the way in which they meet the public.

Like the sculptures in Eva Rothschild’s film, those I have made through the course of this research might themselves be seen as representations. Although they could be considered props, this does not seem to sit correctly. They are not stage properties intended to aid a theatrical or cinematic narrative. They are the subjects of the films, the central focus. Whilst the framing of the objects by the film, and its presentation in an art context, does some of the work of telling us that this is sculpture, the objects themselves are also working to point us to this recognition. They look like sculpture. They have sculpture-qualities. They seem to reference some Modernist tropes and styles; angular abstraction, organic forms and kinetics, among others, but they are not clearly identifiable as copies of particular works.

Now perhaps we come to the nub of it. Because the films do not tell us that these are sculptures in the way an exhibition in a gallery does. The fact that these films are art is affirmed by my identity as an artist, by that of the institution which funds and supports this research and the galleries in which the work will be exhibited, but this is not the point. By reaching the viewer through film, something subtly different is being done. By being there on film, rather than there in person (so to speak), the question immediately arises, why? The films, and the objects they present, are telling us two things at once; that these are sculptures and that they are not quite sculptures. Or at least not quite in the usual way sculpture is constituted.

To further complicate matters, I have, in the latter part of the PhD, begun to show the films I have made on small screens, alongside the objects. These have been presented on table tops inviting viewers to handle and rearrange both objects and screens as they see fit. Prior to this, the films had generally been shown as projections, or on large monitors, which create a certain amount of physical distance to the viewer and emphasise the images as windows onto the objects within them. By showing films on small screens – tablets and smart phones – which already have handling built into their proscribed use, the films take on a certain objecthood in their own right: things in people’s hands, which can be picked up and arranged in much the same way as the objects. At the same time by making the objects available to the viewer to handle a significant sign-post of ‘art’ in the traditional sense - that works of art are not to be touched – is being contravened.

In these encounters another aspect of the objects is revealed to the viewer, which might otherwise be kept secret; that they are only as good as they need to be for the purpose of filming. They are often surprisingly flimsy and lightweight. Sometimes they are not entirety ‘finished’. If the intention was to film them only from one point of view for example, they may not have been painted on both sides, they may not be entirely stable as they only need stand up for a short time in front of the camera (not for the prolonged time frame of an exhibition), they may be marked or chipped attesting to the time they have already spent being filmed and moved around. They have a certain openness to contingency, which again throws into question whether or not these things can be considered ‘sculpture’. Their physical form is, to a certain extent, dependent on their being made to be filmed. Displaying the objects themselves reveals the extent to which they depend on the camera.

In this sense, the closure or coherence of the traditional gallery exhibit as a physical unity, is further undermined as these ‘sculptures’ are again folded back into the larger context of the art making process, of which the encounter between sculpture and camera forms only a part. If we see this process, from initial construction (or conception) of an object, through multiple re-workings and encounters with the camera, reshoots, edits and presentation to viewers, often in multiple and differing ways, then the moment in which the object is recorded by the camera forms a structural pivot, with all activities being undertaken with this moment in mind. So, there is the before filming and the after filming and even the inter filming; there is no part of the process which isn’t in some way inflected by the fact of this encounter. At once we might say that the sculptures are made for the film, and on the other hand, the films are made for the sculptures. They exist in a feedback loop, or mobius strip in which there is a continual back and forth between the sculpture and the film. Neither is the means of the other’s end.

We might return here to Gombrich’s insistence (Gombrich 1985) that representation as substitution predated that of imitation. The objects of this research could be seen to imitate sculpture, but this is undermined by their no- sculpture-in-particular quality. Perhaps we could see them as substitutes. Like the hobby horse they need to be seen not as copies or imitations, but instead to fulfil a practical requirement: in this case that they are fit or suitable to be placed in front of a camera.

If we look again at out reformulation of Gombrich’s statement replacing horse with sculpture, then these sculptures are neither signs signifying the concept of sculpture nor portraits of individual sculptures. By their capacity to serve as a ‘substitute’, the objects on film become sculptures in their own right. This may shed some light on another trend in the research. That the ‘sculptures’ are of a reassuringly familiar size. Small by Modernist standards, they have taken on a camera scale, which is also one related to the hand which operates the equipment and handles the objects, often in close connection if not simultaneously.(In this respect Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Torpedo Fish (Toy) (1914) is an early and important point of reference. Intended as a ‘pocket sculpture’ for the philosopher T.E Hulme it was made with the hand in mind, whether to be used as something to fiddle with whilst writing or more aggressively as a knuckle duster (as suggested by the Kettles Yard website (2014), this is a form of sculpture brought to the proportions of the hand. Similarly at the Chicago Bauhaus in the 1930s Lazlo Moholy-Nagy and his students created ‘hand sculptures’ made not to explore visually but through the sense of touch; an integral part of the artists ‘sensory training’. (Botar 2014, p.27)) My‘sculptures’arethereforetoys,broughtintothegameof filming. They are enough like sculpture to function for the camera and to instigate a certain type of playful activity in front of it. In the end it does not really matter whether we call them sculptures or not, but rather that these diverse lines of questioning uncover the importance of these ‘sculptures’ as objects of use, not of detached contemplation. We have now considered these objects through the lens of philosophy, phenomenology and anthropology. What has emerged is a complex picture: a range of possible understandings and practices with the pictured object at its centre. The question of whether or not these objects are ‘sculptures’ becomes less important than the question of what, as objects, they allow for or instigate. They are the locus of a series of encounters - between objects and cameras, objects and viewers - which have constituted this research, offering ways to think through the complex issues of representation, recognition, art viewing and encounter, practical exploration, play and learning.

ARE THESE TRANSITIONAL OBJECTS?

The strange, neither-one-thing-nor-the-other quality of these objects has led to consideration of Donald Winnicott’s theory of transitional objects, in which he theorises the way in which the infant becomes aware of the external world. Initially the world and objects within it are presented to the infant by the good enough mother (which we must understand to extend to the family and the outside world more generally) in a way that appears to them as self-created; they desire milk, the breast appears. It is essential to our psychic development that these seemingly internal objects, as they are known in Psychoanalysis, become separated from the psyche, in order that the infant can come to understand the world of objects as external phenomena. For Winnicott this is predicated on a paradoxical impulse in which the psychically healthy infant must destroy the object, which subsequently survives. This survival allows the object to gain external existence, the subject placing it, ‘outside the area of [their] omnipotent control, that is, the subject’s perception of the object as an external phenomenon, not as a projective entity’. (Winnicott 1969, p. 713) This is often referred to as the infant’s ability to distinguish between ‘me and not me’. It is with this formulation that objects become unfixed from their specific identity within the psyche and become solid things in the world, which can be manipulated and changed by the will of the infant, as well as by environmental factors.

Winnicott’s transitional objects accompany a specific stage in psychic development and are therefore those close to the infant – the breast, the thumb, a cuddly toy. The concept of the transitional object then does not refer to a specific class of objects, but to a particular use of an object for developmental purposes. It is therefore our ability to separate things from the psyche that underpins our relationship to objects and the external world more generally. It is what enables us to use and manipulate things, and to hold multiple meanings or possibilities for objects within our understanding, without the coherence of those objects being threatened.

We might see this manifest in our relationship to convention and habit within adult life. We are inclined toward generally fixed or glib understandings of, and relationships to, things. This we might see as a type of security which allows us to concentrate our attention on the things that concern us, in the confidence that the world as a whole will remain reasonably stable. However, by the same token we are always able, in principle, to throw open and shift our understanding and use of objects. At times this may be straightforward, at others very difficult, depending on the importance they hold within the structure of our psyche.

For Winnicott, the shift from ‘object relating’ to ‘object use’ underpins our capacity to play. We might see this clearly in the play of children from as young as eighteen months, but it is also in evidence from as early as six weeks. The toy car is used as a phone, the box as a cup, the peas as balls. This ability is predicated on the transition from ‘object relating’ to ‘object use’, which happens through the object’s destruction and survival, and is the basis for our imaginative and creative relationship with the world of things. Critical for the current research is Winnicott’s insistence that analysts take into account the external world of objects, not as projections but as things in themselves. The objects of our concern are therefore not simply empty signifiers given meaning by the psyche, but real objects in the world, which are vitally important for our development and understanding. It is they that structure the infant’s development into psychic awareness and adulthood. Objects enable us to be human.

How can we make sense of this in relation to the objects I make to film? When being filmed, they are literally in transition, from three-dimensional real-world objects to two-dimensional pictured ones, from inanimate to animated, inactive to activated. Equally transitions can happen within the films, where an object appears differently through the course of its time on screen. Whilst they cannot be transitional objects in the precise sense in which Winnicott uses the term, we might draw some useful parallels.

If we were to think of them as transitional, then these objects must have a certain degree of significance. Certainly, they have significance within the context of this research. As I have already said, they are not stage properties, they are the central focus and subject matter. They also have a distinct importance to me. They are the objects of my work, they are precious and have a direct bearing on my sense of self. Yet they are not fixed in this respect. They are important because of the activity they inspire and, as has already been noted, they are somewhat indeterminate. They could easily be a little different and still function as well within the framework of my artistic practice. They are objects which invite play and physical manipulation. They are things to which I have a sensual as much as an intellectual relationship, many of which seem to have prompted forms of touch and physical handling. As part of the dynamic process of filming and performing in front of the camera, they are also immersed in a context which prompts change, manipulation and difference, and which does not have a clearly articulated end-point. It would always be possible to make another film. They are objects which seem to be in constant or frequent transition, or which are at least transitional in principle.

For my own part this places me in a different relationship to the objects of my work from, for example, an artist working towards clearly defined pieces, which are seen to be completed and from which the artist must move on. The things I have made linger, hang around in my studio; it is always possible for them to be reused and reactivated. They do not have meaning as object or sculptures in themselves, outside their particular history of use; the shoots I have taken them on, the things that happened to and with them, and the images which were created.

The question then arises, how does this importance function for other people? Is something of this altered relationship retained in the film footage? Is it necessary for people to come face to face with the actual objects, to take part in the process of manipulation? If they do join me in playing with and filming the objects, do they have, in any way. the same type of relationship to them as I do?

Throughout the research there have been many opportunities to present the films and objects in different ways – as single and split-screen film montages, alongside text, on tables, as gifs. The aim has never been to present a clear definition, as if these objects were complete independent things, but to offer the viewer opportunities in which to understand these as objects, which are in some way mutable, changeable or in transition. It aims for the mode of presentation (as with that of the making process) to be one which poses questions in a playful manner, drawing the viewer into a conversation about exactly what it is they are looking at.

Perhaps this goes some way to explain the importance of film and video over that of photography within the research. Moving image is a place where things can happen, where an object can be presented and then nudged or moved or in other ways re-articulated through physical interaction, shifts in lighting or viewpoint. As opposed to a photograph which fixes an object in a particular aspect, in moving image, things are able to change, and the process by which the objects are presented, becomes a part of the viewer’s perception and understanding. Film’s temporal aspects allow for these objects to retain their mutable and propositional character.

By referring to these objects as ‘good enough sculptures’ the intention is to highlight these aspects. It is hard to imagine a sculpture in a gallery being described as ‘good enough for a plinth’. This would immediately undermine any sense in which the object was worthy of artistic consideration in a system which reifies ‘works of art’ as cultural artefacts of significant value in and of themselves. We might see the imposing bronze on a plinth as an object to which we can relate, but not use. It’s meaning and our relation to it has been fixed by social prescription and convention. We may judge its merits and form an opinion of them, but we cannot easily use them to play.

As has been said earlier, the object of this research is not intended to be fixed and finished sculptures, or objects for detached contemplation. As objects of use they are poised to be taken up and manipulated, explored and reframed within the artistic endeavour, whether this be as artist, spectator or participant. As Psychoanalyst and Winnicott scholar Jan Abram notes in the closing gambit of her paper Interpreting and Creating the Object, ‘[b]oth the ‘artistic endeavour’ and ‘the act of psychoanalytic endeavour’ offer infinite possibilities to evolve and continually become the Self we are always in the process of becoming... up until, and hopefully at the moment, we die.’ (Abram 2017, p. 9)

As objects made to prompt thought and exploration, these sculptures made to be filmed are in a continual process of becoming, with no definitive end other than that of the film ending, the camera turning off, time running out. Whilst these specific sculptures may live on beyond the current research, it is the spirit they embodied that is of importance: the continual turning over of ideas and materials and the ethics of never reaching a fixed conclusion. They embody an invitation to explore and transform, to engage in physical, material and imaginative processes of investigation, in the confidence that new forms of art and knowledge will be created, new relationships made, new identities formed.

This brings us back to our earlier discussion of heurism and to Addison’s teacher as a facilitator of environments, in which students can find out and come to know by challenging their preconceptions. Similarly, as Abram (2007) notes, Winnicott appeals to the analyst to refrain from interpretation, to allow the analysand to reach understanding through the process of analysis. A view of psychoanalysis in which the ‘analyst’s task is to facilitate a space within which the child or the patient is able to discover something for [themselves].’ (Abram 2007, p. 257) For Winnicott analysis is a ‘highly specialised form of playing’ (ibid, p. 256) predicated on the idea that it is through play ‘that children [...] make external the world’. (p. 252) The job of the analyst, as with that of the mother (or care giver) is to provide a good enough environment, populated with good enough objects, in which the infant feels safe and confident to take risks and explore. What is significant is not the analyst’s (or the artist’s) clever interpretation, but ‘The significant moment is that at which the child surprises himself or herself.’ (ibid, p. 256)

As with the presentations, workshops and exhibitions I have organised through the course of this research, to read this, I hope, is to enter into the dialogue in which I have been engaged, and through which my knowledge and understanding has grown; knowledge and understanding born of experience, characterised by a process of continual evolution with objects as my playthings, and conspirators. In this sense the research facilitates opportunities for people to explore their own conceptions and hopefully provides contexts in which fresh discovery is possible.

❮ ❯

For three years this enquiry proceeded under the question ‘what happens to sculpture when it is filmed and photographed?’ While this question, in the end, became inadequate to describe the specific trajectory the research took, it was incredibly generative. It enabled me to convey easily a sense of my enquiry to others and, by continually coming back to it again and again, it structured a collection of activities which have ultimately outstripped it and its usefulness, but to which it will always be indebted. The main problem as it turned out was not the question’s breadth (this was always understood), but in its use of the word ‘sculpture’, which in the end seemed to signal something which did not exist. There was no sculpture to begin with that things happened to, no original to which all images could be compared. The sculptures of this research, – and as we shall see this is no simple definition – the things I have made, were not ‘sculpture’ before they were filmed. Conceived of and constructed for the process of filming they are sculpture made to be filmed but also objects made to be sculpture. They are the instigators or loci of a series of practices aimed at generating questions about the nature and possibilities of these objects within an artistic practice structured around the camera. ‘Filming sculpture’ becomes the situation/set-up which organises the production of objects-as-sculpture in ways that throw light on, or open questions around, both sculpture (as a particular category of object) and objects more generally....

We therefore turn our attention toward the ‘sculptures’ of this research and to the question of what they are, how they should be considered, and what exactly is the function of their relationship to the camera.

It seems important that these objects have been physically constructed or formed. They are not consumable objects plucked from the world in the sense of the ‘readymade’, bestowed with sculpture-hood by the art context. Nor are they everyday objects explored for their physical and imaginative possibilities such as in the film Plasma Vista (2016) by Cockings and Fleuriot, or the films of my own collaborator Claire Undy. Neither are they assemblages of objects presented as sculpture, like the photographic series Equilibre (1984-7) by Fischli/Weiss, where the camera is used to bestow a permanence on momentary or short-lived constructions. Similarly they are not objects from other disciplines such as design or architecture, which are of particular formal or aesthetic significance that the camera can draw attention to, like Simon Martin’s Carlton (2006), in which a piece of post-modern furniture is beheld enigmatically and beautifully on film, or transformed by the use of lighting like Hollis Frampton’s film Lemon (1969), in which a giant fruit is slowly revealed as if it were a moonrise. They are not interventions into everyday life recorded by the camera, such as Cats and Watermelons (1992) by Gabriel Orozco, or the films of Francis Alys, or performance acts which have been documented, like those of Bruce Nauman and Claes Oldenburg.

Despite not being exactly like any of these practices, the current research benefits from engagement with them all. It borrows strategies and processes and applies them to its specific concern: how the physical forming of a sculpture can be placed in a reciprocal dynamic with the act of filming. The question is not whether the camera legitimises these things as sculpture, but rather in what ways can the dynamic of sculpture and camera be employed in order to explore their combined possibilities.

The objects of this research have been made – constructed, modelled, carved, cut – by the artist in order to be filmed and this gives them a very particular quality and status. Although they are not intended for presentation within a gallery space, they do look very much like sculpture. They are things which have mass and weight and particular aesthetic qualities of a sculptural kind.

A series of questions then proliferate: Does this sculptureishness pre-exist the filming of the objects or is it conferred on the objects by the process itself? Are aspects of both objects and process conspiring to produce sculpture effects? Are they significantly different things than they would be if they were intended for a more traditional mode of display?

This ontological questioning owes much to readings in contemporary metaphysics and phenomenology. This is not questioning that demands definitive answering, but has been used to tease out the particularities of the research process, and of the objects and practices which comprise it. We will return to the particular properties which might be seen to characterise these objects as ‘sculpture’, and turn now to their relationship to the process of filming, and questions about the nature of objects in general. When we talk of these sculptures what exactly is it we refer to, the physical object which is placed in front of the camera, or the thing which reaches the viewer on or through film? Are these to be considered different objects, or instances of the same? Do they persist as relatively stable entities through the process of filming or are they transformed into something substantially different to that which they originally were?

THE REAL AND THE SENSUAL

Object Oriented Ontology and the related areas of Speculative Realism, Thing Theory and Vibrant Materialism, have all come to prominence in recent years, and have been widely embraced by the art world. What unites these philosophies is their consideration of a world of objects existing beyond human access, in which objects have hidden depths and vitality, or exist alongside humans in networks where agency is dispersed.

A number of strong criticisms have been made of these philosophies, including that they have been all too easily co-opted by the art market and ‘stripped for buzzwords’ (Apter etal. 2016, p.8) in order to reaffirm the commodity value of art works, and that by focusing on objects, these philosophies ignore the still very real and ongoing political inequalities that exist for people, which post- structuralist inspired theories did so much to challenge.

The use of vivid and poetic language employed by many of these writers can also be problematic as it can be seen to lead to a kind of object fetishism, which marvels at the glories of matter and material in a mysterious and anthropomorphic, even quasi-religious, manner. What D. Graham Burnett describes as, ‘barely secularised forms of spiritual striving.’(ibid, p. 20) The refreshed attention given by artists and curators to the potency and depth of art objects in the wake of these philosophies, would seem to support this idea and can easily be seen as a form of reification, if not a directly monetary one. This aside, by shifting our focus away from the ways in which sculptures are made and intended by human agency, and instead considering the latent qualities and dynamics between sculpture and camera, and the ways in which they impact upon the various encounters that make up the full scope of the art work – from conception, construction, filming and editing to its meeting with a viewer - these philosophies offer us the opportunity to form a deep and complex understanding of this process and the objects that constitute it. As Armen Avanessian writes, ‘[t]he thing about the toy truck, for the magnet, is the iron. The thing about it for the girl (just now) is the sound the wheels make when they spin really fast. The thing about it, for her mother, is the fact that her own father once played with it, found it, repaired and repainted it (yellow). The thing about it, for the cat, is that at any moment it may dash like a rodent. Some latent thing about the object must be catalyzed by an encounter, and yet: that very thing catalyzes the encounter. (ibid p. 8)

This duality, or paradox is at the heart of Graham Harman’s Object Oriented Ontology, which sees objects as both embedded within a field of relationality and coherent as things in themselves. In order to articulate this joint existence, he posits two types of object, the ‘real’ and the ‘sensual’. The real object is that which forever withdraws, exceeding any relation. The sensual object is that which is created within the relational encounter. These two facets of the same thing allow objects to appear differently, dependant on situation and circumstance, without the coherence of the object itself being threatened. Here the tree is the same tree in summer and in winter, with or without foliage, from close up and at a distance. This is because the tree has a reality which exists beyond any single perspective or perception. Objects therefore, have two types of quality. Those which are susceptible to change and which the object can withstand, such as variations in light or the loss of leaves, and those which are essential to it. Here we might imagine that a tree reduced to firewood or to ash, is no longer a tree. Harman writes that accidental qualities ‘can be shifted nearly at will without affecting the character of the object. Yet the same is obviously not true of its essential features, which the object desperately needs in order to be what it is.’ (Harman 2011, p. 27)

In the context of this research, a model is offered with which to consider the sculpture on film. We could describe the sculpture made to be filmed as the ‘real’ object, which when filmed is given a number of accidental features which inflect our perceptions of them, but which the object can survive – we might think of the mottled texture of 16mm film, the use of harsh lighting, or different camera angles. The object is changed but not unrecognisable. The film could be seen to offer the viewer a series of sensual profiles in a similar way to that which we would find were we to encounter the object in physical reality. What is interesting is that Harman sees these sensual profiles as infinite possibilities. Each and every perception (and this goes for interactions between inanimate objects as well) unlocks only certain features of the object. This allows us to think of the process of filming, not as one of loss – the compacting of three dimensions into two, the fixing of a particular spatial and temporal view - but of unlocking features of the object which may otherwise have not come into view, for example the intense sense of texture that can be produced by harsh lighting and extreme close-up, or the seductive quality of a white, angular object against a stark black background.

For Harman, objects are only ever encountered as sensuous profiles and as such our perception of objects is inevitably partial and our expressions of them – their descriptions or representations in art, philosophy or science - can produce only caricatures, partial renderings masquerading as fully present. The use of the term caricature is, however, somewhat misleading as it suggests that sensual objects as they are perceived are in some way superficial, trivial and simplistic. In fact, the sensual encounter can be multi-layered, deep and complex, a swirl of accidental and essential features, but there are always further possibilities which will be revealed in other encounters. The object is never exhausted.

The universe is thus full of objects which continually withdraw, as there are always aspects of the object which do not present themselves in any single encounter. By this reckoning there could be an infinite number of films made of an object, each unlocking new and different aspects of the thing, never exhausting its possibilities. Harman has more recently replaced his use of the word ‘withdraw’ with that of ‘withhold’, but both have the same mysterious connotation which is appealing in relation to the current research. Art objects are often thought of as compelling because of their depth and inscrutability. The project of art history is in a sense the quest to delve into these myriad possibilities. In this sense however, it is the art historian who is actively probing the work, which may otherwise be considered stable, fixed and complete. In Harman’s hands, it is the object that is the one doing at least some of the work of withholding and revealing, the process is a dynamic one, characterised by negotiation and collaboration.

The complex physical interrelation between camera and object may be further developed in relation to Merleau-Ponty’s evocative description in Eye and Mind (1993) of seeing the tiles at the bottom of a swimming pool: ‘When through the water’s thickness I see the tiling at the bottom of the pool, I do not see it despite the water and the reflections there; I see it through them and because of them.’ (Merleau-Ponty 1993, p. 182) Rather than obscuring the full reality of the object it is the stuff which surrounds it which enables the encounter.

Consider light rather than water. The particular colour frequency may affect the way in which an object is seen, without it there would be no sight. Here the object is inseparable from the watery medium which is at once transparent and viscose. We might see a similar conception in Husserl’s notion that we do not see black, we see the black of ink, or the black of tar, except here the focus is reversed. In both cases objects and qualities are intertwined and inseparable and always embedded within a wider perceptual reality or world, which includes the body, prior experience and socio-historical, cultural and technological conditions. These things are inseparable in our perception.

A similar operation is at work in Harman’s critique of scientific rationalism, which he describes as undermining the object by searching for a more basic reality beneath its surface, and philosophies of relation, for overmining the object, reducing it to its position within a contextual network. Instead he sees the object as caught in a dynamic relation between its inherent reality and the specifics of the situation in which it is found.

An argument could be made here from a Marxist perspective that Harman’s ontology ignores history, or at least subsumes it within the generalising framework of objects and relations on the one hand and objects and qualities on the other. If we consider the reality of objects (and sculptures more particularly) within the frame of art history or culture more generally, then existing in a highly developed consumer society, as we do in the West, is yet another pool through which we see and into which all objects are immersed. This includes multiple discourses from the financial, economic, personal and ecological. The endangered tree has a different patina to it than the common one: its material presence is altered by countless contextual relations.

More surprisingly in Harman’s reckoning, every relation no matter how trivial creates a new object, as within each sensual encounter there are aspects which do not come to light and must, in Harman’s reckoning, constitute a new real object. This makes for a complex situation when filming sculpture. It would appear that in each encounter between sculpture and camera both new sensual and real objects are produced. There are two real objects to begin with: the camera and that which is placed in front of it. The sensual object is what is recorded: an image of the object placed in front of the camera. A new real object is produced: the film which then goes on to produce sensual profiles when encountered by different viewers under different circumstances (more sensual objects).

But there is also the sculpture pictured within the film, which is where the real discoveries of this research may lie. Is this merely another sensual object, one of many potential caricatures of the ‘real’ thing that exists as a physical reality somewhere beyond the film’s reproduction? Or has something new been created, something with its own distinct reality?

If we think of the process of filming as a transformative act, one which not only changes the appearance of the sculpture but potentially transforms the sculpture-like object, the thing made to be filmed but not exhibited, into something that is recognised as sculpture, then something more profound is taking place. The film both reveals new aspects of the sculpture/object and creates a new object: the object as sculpture.

Harman’s litmus test for a real object is whether it has qualities which exceed the sensual encounter. The question is whether the pictured object is all used up when it meets the viewer – does the camera lock down a particular and partial view which is grasped in the same way no matter how, where and in what way it reaches the viewer - or can different qualities be perceived in different circumstances or modes of viewing? For example, if it is projected on a large screen, or on a hand-held device, shown physically side by side with other works or sequenced as part of a larger film.

To further complicate matters, I would suggest that this is not a temporal transformation. The object is not simply an object which is then transformed, butterfly-like, by the process of filming. By being a sculpture made to be filmed, the object owes its sculpturehood to the camera from the very outset, with its own highly-particularised reality. We can then see that we have only one object: the sculpture made to be filmed which can be encountered sensuously by the camera, the artist, the viewer and the workshop participant, in actuality, or on film, each iteration revealing different aspects inherent to the infinitely withdrawn, or withheld ‘real’ object.

Whether we think of the sculpture made to be filmed as a singular real object with a multitude of potential actualisations, or as the process of filming creating a new object, these lines of thought allow us to imagine the confluence of object and camera as a constitutive act, in which something is produced which exceeds conventional understandings of both camera, as that which sees and reproduces, and sculpture, as that which has a singular physical reality outside of the film process.

It may also be that the camera alone does not have the power to confer sculpturehood upon these objects. It is part of a contextual framework which designates certain objects as sculpture, combined with certain sculptural qualities of the object itself. This includes among others, the figure of the artist, the recognition of film and video as an artistic medium, the context in which the work is encountered, and the institutional framing. Rather than trying to make a claim as to whether the pictured sculpture is a sensual or real object, this line of enquiry helps us to form an understanding of the complexity of the relationship between the many factors which condition the work with the moment of filming at the centre.

Rather than seeing the camera and sculpture standing in fixed relations, augmented by human agency, the camera perhaps being seen for its utility in the act of creating images, conceived of and realised by the camera operator and equally the sculpture as a piece of, or combination of, physical materials, forged by or subjected to human will, we can focus our attention on the qualities that each bring to the situation. The ways in which they condition or inflect our approach and understanding of them as entities with a certain degree of agency. Both in their physical, sensual reality and in the ways in which they embody certain aspects of culture more generally. This can lead us both to consider Michel Serres’ concept of the quasi-object and Willem Flusser’s description of the camera as an apparatus encoded with a pre-given set of cultural instructions which the photographer must negotiate.

Flusser writes that, before the industrial revolution, tools were used by humans as extensions of the body. In industrialised capitalist society, however, the human became a function of the machine. The camera operator is thus a functionary who plays with the machine in order to discover its possibilities, which are already pre-determined by the concepts by which the machine was constructed. The photographer (and we may extend this to film-er/video-er and artist) ‘plays’ with the apparatus, which by inference involves playing with the symbols which are programmed into it by ‘meta-programs’ of ever increasing scale – from the science of optics to economics. Sounding remarkably like Harman, Flusser writes, ‘The possibilities within it [the camera] have to transcend the ability of the functionary to exhaust them [...] no photographer, not even the totality of photographers, can entirely get to the bottom of what the [...] camera is up to. It is a black box.‘ (Flusser 1984, p. 27)

This Marxist view has similarities with Michel Serres’ description of the quasi- object. Like Flusser’s apparatus, the quasi-object structures a game conferring subjecthood upon the players. Speaking of a game in which people must pass around a button or slipper without being caught, Serres writes, ‘[t]his quasi- object, when being passed, makes the collective, if it stops, it makes the individual.’(Serres 1982, p. 225) The subject (or subjects) and the object are here mutually constitutive although, as he says of the football, it is the players that follow the ball not the ball that follows the players. ‘Playing is nothing else but making oneself the attribute of the ball as a substance.’ (ibid, p. 226) As with Harman’s objects, Serres is concerned both with the quasi-object as an entity in itself and as a relation: ‘Being or relating, that is the whole question’ (ibid, p. 224)

OBJECTS AS AGENTS

Something similar to Serres’ quasi-object can be found in the concept of indexical agency in Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency: an anthropological theory (1998). Concerned not with philosophical classification, nor sociological concern with institutions and systems, but rather with causal relations happening in real time, Gell shows that objects can be seen as embodying a dispersed social agency. In the first instance this can be seen as a question of identity: for Gell the soldier cannot be a soldier without rifle and land mine, objects which enable him/her to express their causal agency and retain a connection to them beyond their direct presence. Thus the landmine explodes despite the soldier’s absence, but they are nevertheless the agent of this destruction and the harm it may cause. The landmine functions as an index because this causal agency is seen as directly imprinted upon or expressed through the object. It is also the case that ‘agents’ and ‘patients’, as he calls the affective and affected parties in any social relation, continually interact though physical substrates (the body, tools, the material environment) without which no action could be set in motion. Actors in social relations (which include objects) continually slip back and forth between agent and patient status. Importantly for us, Gell talks not in philosophical but biographical terms. For him it is of no consequence that his car does not possess agency in the philosophical sense, what is important is that in day to day life the car is treated by him and his family as if it had partial agency. It is what they rely on to get around: if it were to break down he would consider this an affront; he may even blame the car or kick it; it is even referred to affectionally by a nickname. If we think back to artist Jo Addison’s description of learning her sculptures by making them, we may find something similar in operation. For her, in practice, the objects she makes are attributed a kind of agency, they direct her material investigations, they ‘tell her’ how to progress. More prosaically we might say that the material properties of the objects she creates impact upon her handling and forming of them. They push back. They will hold certain forms and not others. The process of making thus becomes a back and forth of agency, as the agent-patient relationship flips back and forth between artist and object.